The shoulder has the greatest degree of motion of all joints in the body. It is a ball and socket joint in which the ball is the humeral head (proximal humerus) and the socket is a part of the scapula called the glenoid. However, because the glenoid is nearly flat the shoulder joint relies upon important soft tissue stabilizers one of which is the muscle and tendon complex called the rotator cuff. The rotator cuff has two functions; 1) position the humeral head near the center of the glenoid while stronger muscles such as the deltoid, pectoralis major, and latissimus dorsi move the arm, and 2) assist in movement of the shoulder such as reaching behind your back (internal rotation/subscapularis), reaching behind your head (external rotation/infraspinatus and teres minor), lifting your arm to your side (abduction/supraspinatus), and lifting your arm in front of you (forward flexion/supraspinatus). The rotator cuff is composed of four individual muscles whose tendons meld together to form a cuff of tissue that attaches to the top of the humerus. These fours muscles are the:

Additionally, there is a fluid filled sac called a bursa between the rotator cuff and the bone on top of your shoulder (acromion). The bursa allows the rotator cuff tendons to glide freely when you move your arm. When the rotator cuff tendons are injured or damaged, this bursa can also become inflamed and painful.

A tear in the rotator cuff is a common cause of shoulder pain and disability among adults. Tearing the rotator cuff can cause pain, weaken your shoulder and limit the ability to move your arm. This can make many of the common things you do during the day painful and difficult to accomplish. Activities such as combing your hair, brushing your teeth, getting dressed and reaching overhead all require your rotator cuff.

A torn rotator cuff tendon is no longer fully attached to the humerus and depending on the extent of the tear, the muscle may not be able to fully move your upper arm. Most tears occur in the supraspinatus tendon and affect your ability to raise and rotate your arm. Sometimes other muscles are involved more commonly the infraspinatus or subscapularis. Over time, tendons may fray and as the damage progresses, may completely tear or at times one traumatic injury can cause a tear.

There are different types of tears.

There are two main causes of rotator cuff tears: traumatic injury and degeneration.

Acute Tear

These are a result of an acute traumatic injury such as falling on an outstretched arm, or lifting something too heavy with a jerking motion which can tear the tendons that make up the rotator cuff. This type of rotator cuff injury may also occur with other shoulder injuries such as dislocations and broken collar bones

Degenerative Tear

Over your lifetime, the tendons slowly wear down. This is a natural part of the aging process and occurs more commonly in your dominant arm. A degenerative tear in one arm places you at higher risk for a tear in the other arm. Several factors contribute to degenerative, or chronic, rotator cuff tears.

Risk Factors

Wear and tear with aging means that people over 40 are at greater risk of rotator cuff tearing. Most younger people who injure their rotator cuffs do so as a result of a traumatic injury such as a fall. Carpenters, mechanics, painters and others who do repetitive overhead activities have a greater chance of having rotator cuff issues. Tennis players, baseball pitchers, and other ball sports athletes are vulnerable to overuse partial thickness tears while participants of contact sports are at higher risk of acute tears.

Rotator Cuff Tear Symptoms:

The most common symptoms of a rotator cuff tear include:

A sudden tear will usually cause intense pain and may be associated with a snapping sensation and immediate weakness in your upper arm. A rotator cuff injury can make it painful to lift your arm out to the side.

Tears that occurs slowly over time due to overuse can also cause pain and arm weakness. You might have pain in your shoulder when doing overhead activities or when you reach for items. Over-the-counter medication, such as aspirin or ibuprofen, may relieve the pain at first.

Over time, the pain may become more noticeable at rest, and no longer goes away with medications. You may have pain when you lie on the painful side at night. The pain and weakness in the shoulder may make routine activities such as combing your hair or reaching behind your back more difficult.

After a discussion of your general medical history, your doctor will ask you about your shoulder’s history including injury history, prior surgeries, duration of symptoms, disabilities related to your shoulder, location of pain, duration of pain, and aggravating and ameliorating activities. Additional information regarding previous treatments such as rest, activity modification, use of anti-inflammatory medications, and any physical therapy is helpful to the treating doctor.

A physical examination will be performed focusing on the following 5 general areas:

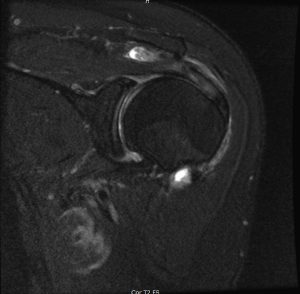

Other tests which may help your doctor confirm your diagnosis include:

Treatment depends upon the severity of the symptoms and the size of the rotator cuff tear. Additionally, the duration of rotator cuff tear can affect your doctors to perform a repair. For partial thickness tears, small full thickness tears, or large chronic tears nonoperative therapy such as rest, activity modification, anti-inflammatories, and physical therapy can improve pain and function.

It has been shown that rotator cuff tears can get larger over time. Early treatment can prevent your symptoms from worsening and prevent muscle degeneration. Once a muscles tendon is completely torn from the bone, that muscle no longer has any structure to maintain its normal resting length. If a muscle is allowed to remain retracted it will undergo degeneration with fat and scar tissue replacing the muscle fibers. Once this degeneration occurs, repair of the rotator cuff tendon may not be possible.

Nonsurgical Treatment

In approximately 50% of patients, nonsurgical treatment plans improve pain symptoms and improve shoulder function, however, strength does not usually improve without surgical intervention. Nonsurgical treatment may include any of the following:

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment may be recommended by your doctor, especially if your pain does not improve with nonsurgical intervention. Continued pain is the main indication for surgery. Your doctor may also suggest surgery if you are very active or you use your arms for overhead work or sports. If you have a large tear (greater than 3cm, your symptoms have persisted for 6-12 months, you have significant weakness and loss of function in your shoulder, or you tear was caused by an acute injury, then surgery may be a good option for you.

Surgery is performed to re-attach the tendon of the rotator cuff to the head of the humerus. There are several options for re-attachment that will be discussed with you by your surgeon. The best approach should match your individual health needs.

Several options are available for repairing rotator cuff tears. The type of approach used depends on the surgeons experience with certain procedures, your specific anatomy and the quality of the tendon and bone tissue. Many surgical repairs can be done as an outpatient and do not require overnight hospitalization. Other shoulder problems may also be present in your shoulder and your surgeon may be able to take care of those problems at the same time as your rotator cuff repair.

The three most common techniques are traditional open repair, arthroscopic repair, and mini-open repair. In the end each technique has its own advantages and disadvantages. Each has the same goal of repairing the tendon and promoting healing. Each method has been rated the same as far as patient satisfaction, pain relief, and overall improvement in strength.

Arthroscopic Repair

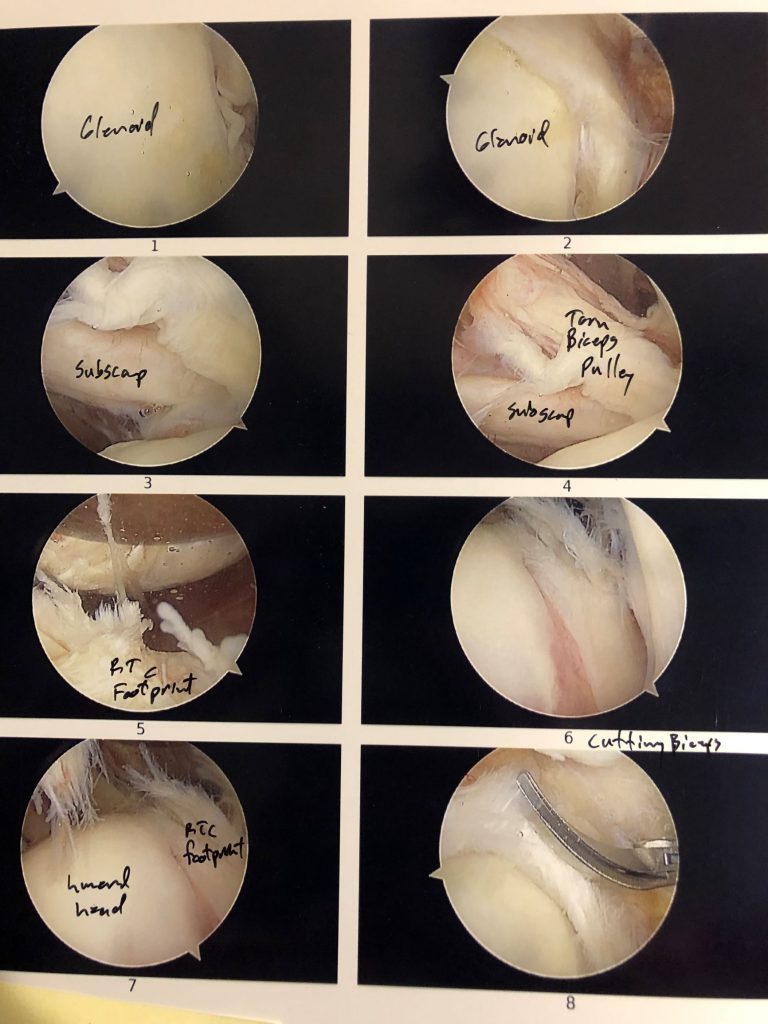

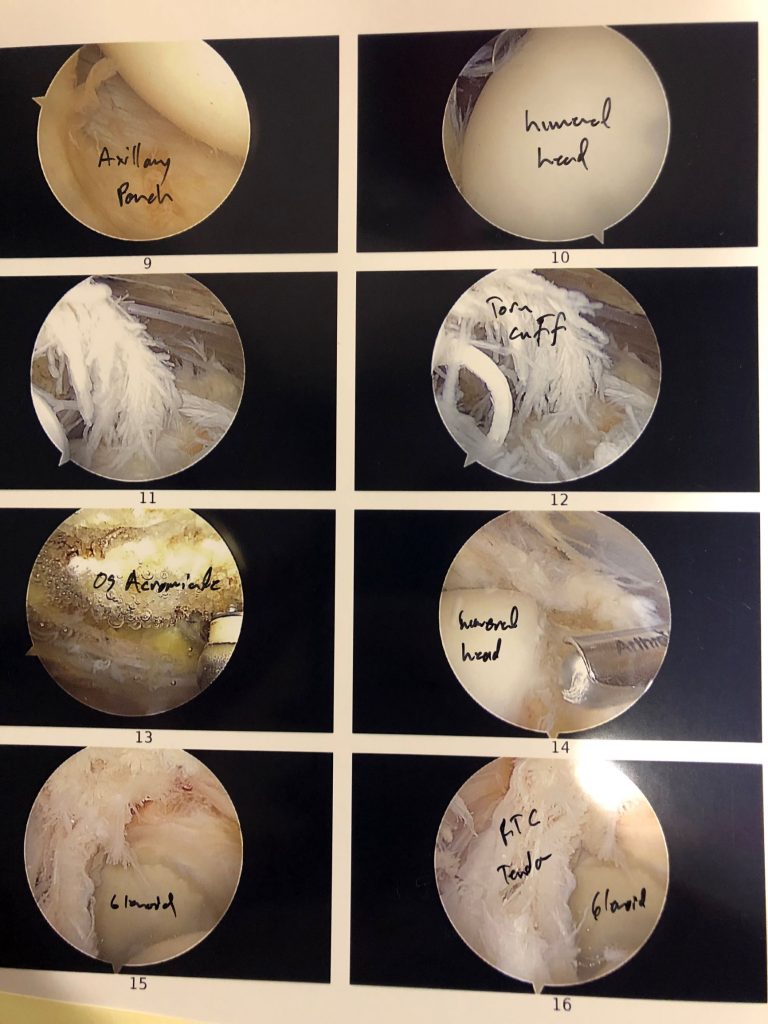

Arthroscopy is a procedure in which a small camera is inserted into your shoulder joint through four or five small incisions which are on average ½ of a centimeter in length. This allows the surgeon to approach your shoulder injury from the inside using tiny surgical instruments. This is a less invasive method for repairing defects in the shoulder. The postoperative pain may be less as well as healing time may be shortened through this approach in compared to other techniques.

Open Repair

A large or complex tear may require a traditional open approach. A larger incision is made over the shoulder and the deltoid muscle of the shoulder is detached to expose the torn tendon. At the same time an acromioplasty may be performed, this procedure is needed to remove bone spurs are removed from the underside of the acromion. A tendon transfer may also be required in order to increase the strength of the rotator cuff repair, often times this is more easily accomplished through a traditional approach.

During arthroscopy, your surgeon inserts the arthroscope and small instruments into your shoulder joint.

(Left) An arthroscopic view of a healthy shoulder joint. (Center) In this image of a rotator cuff tear, a large gap can be seen between the edge of the rotator cuff tendon and the humeral head. (Right) The tendon has been re-attached to the humeral head with sutures.

Mini-Open Repair

A mini-open repair uses a combination of arthroscopy and an open repair approach. Arthroscopy is used to evaluate shoulder and make any repairs within the joint, then the rotator cuff is repaired through a small incision on the shoulder. This avoids the need to detach the deltoid muscle and improves healing time.