ACL Ligament Injury

Background

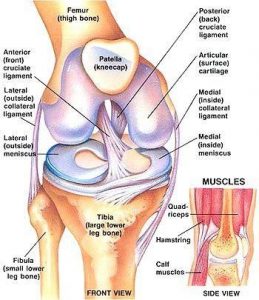

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the major ligaments in the knee. It is located in the center of the knee, with attachments on the lateral aspect of the femoral notch of the lateral femoral condyle and inserts just in front of the intercondylar eminence on the tibia. It’s main function is preventing the tibia (shin bone) from translating anteriorly (to the front). It also helps with internal rotational stability of the tibia. Overall, the ACL provides roughly 85% over the overall stability to the knee.

ACL Injuries

screw in the tibia and the graft (dark

gray structure) between the femur and tibia

The ACL is the most commonly injured ligament of the knee. Approximately 70% of all ACL injuries occur from non-contact activities with most of these occurring in athletes performing a sudden deceleration, landing or pivoting movement. A high risk position of the knee during these events tends to occur when the knee is in a valgus position (knock knee) and in slight flexion. This position tends to occur more commonly in females.

When an ACL rupture occurs, the patient will often recall a “pop” followed by swelling and a sensation of instability. When the initial pain and swelling occurs, the patient may complain of the knee “giving out” predominantly when most of the body weight is on the injured knee such as negotiating stairs, squatting, or pivoting/changing directions. Often times when an ACL injury occurs, there can be associated injuries to the meniscus and lateral tibial plateau.

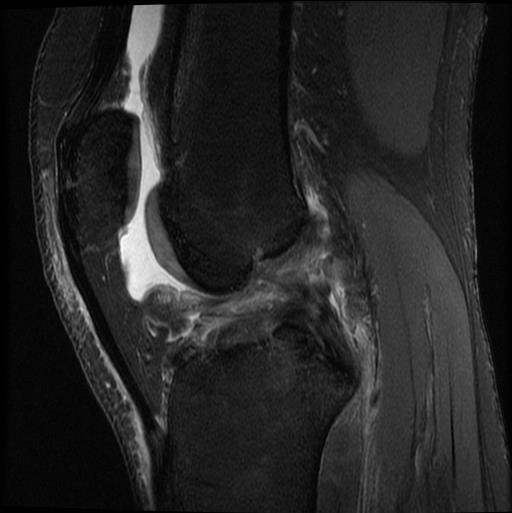

If your provider suspects an ACL injury after examination, they will order an xray and likely an MRI to further evaluate the knee. The xray is ordered to assess any bony injury that may have occurred. The MRI will give a more detailed assessment and understanding of the injury to the bone and soft tissues of the knee.

Treatment

Treatment of an acute ACL tear varies depending on patient activity, life demands and perceived laxity to name a few. Concomitant injuries can also play a role in determining if surgery is required. In a relatively inactive older patient who does not require high demands on the knee and if there is no perceived instability, then ACL surgery may not be required. However, in younger patients, there is perceived instability of the knee or those who are quite active, ACL reconstruction is recommended. ACL reconstruction is generally an outpatient procedure.

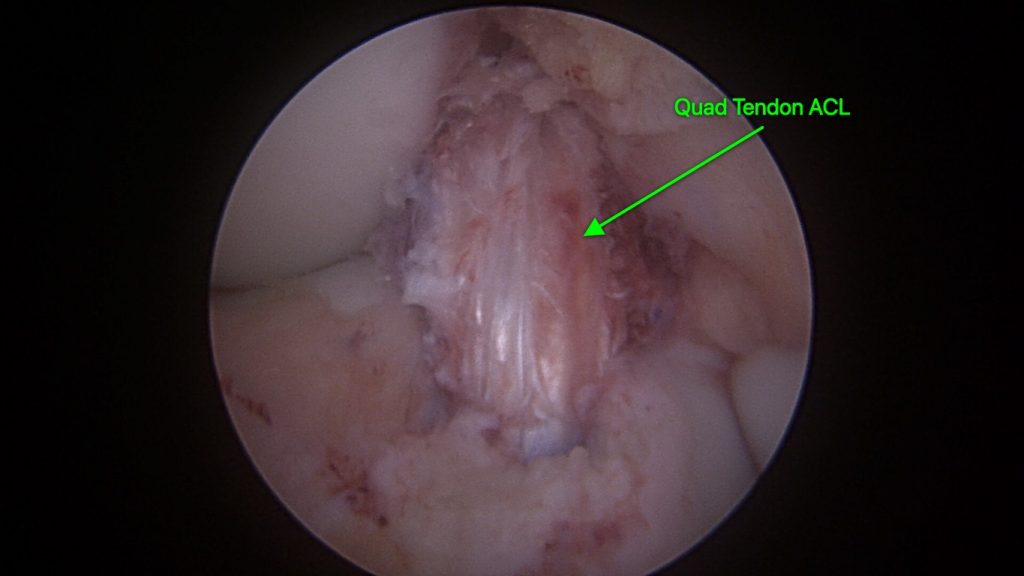

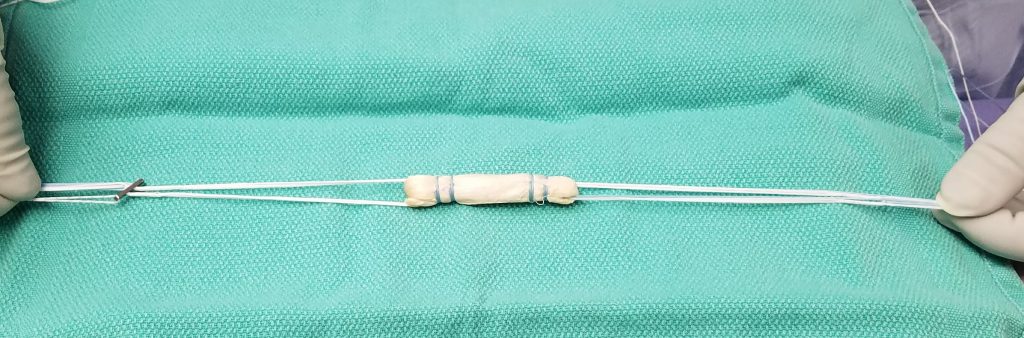

Once reconstruction is chosen, your surgeon will discuss various methods and graft types to reconstruction the ACL. Graft options include autograft (taken from the patient) and allograft (taken from a cadaver). In a younger patient, autograft is often selected and in an older patient allograft is most likely to be chosen. Your surgical team can discuss options with you.

Surgery is the only option to be able to repair the ligament completely but there are different grafts that you can choose from and depending on your age, there might be a better graft to choose. There is the patellar graft from your own patela tendon, there is your own hamstring tendon to choose from or you can also get an ACL graft from a cadaver.

Below is a link to view how the ACL is grafted and fit to the knee

Rehabilitation

In general, rehabilitation follows a few principles: protect the repair, regain motion, maintain patella mobility, and rehabilitation of the quadriceps muscle. The complete rehabilitation process can take several months and full return to play usually occurs around 9 months to a year after surgery. Sometimes, this may need to be extended based on the strength of the quad and hip muscles as assessed in return to sport testing. We generally advise the use of an ACL brace up to a year after surgery when performing dynamic testing or during competition. Below is the general protocol that Dr. Lee follows.

Immediate Postop:

- keep leg elevated

- ice

- patella mobilization, quad activation, and ankle pumps

- No pillow under the knee for 6 weeks – this is to prevent a flexion contracture

Week 1-6 (Restore ROM)

- PROM, AROM

- Wall slides

- Quad sets (no weight)

- Terminal extension

- Stationary biking – the non-operative leg only is used to power the bike for the first 2 weeks. At 2 weeks okay to use both legs with no resistance.

- Can start full weight bearing once the knee achieves full extension and the quad is firing appropriately

- Knee immobilizer when out of bed for first 4 wks.

Week 7-12 (Start Strengthening)

– Sport brace only to be worn during activity

- Closed-chain strengthening

- Gait training

- Double leg strengthening

- Double leg squats to 45 degrees

- Double leg bridges to strengthen gluteals

- Balance Squats at week 10

- Single leg strengthening

- Stationary biking – both legs with increasing resistance

- Aquatic Training – NO breast stroke

- Single leg balancing in extension

- Lunges at week 10

Week 13-18 (Strengthening & Activity training)

– More aggressive strengthening

– Elliptical may begin at week 13

– Stair stepper may begin at week 16

– Proprioceptive Training

– Jogging starting at week 16 inline, flat ground, NO cutting, NO sprinting

Week 19 and on (Sport Specific Training)

– Start more aggressive in-line training

– Initiate light and controlled plyometrics

– Initiate cutting, cross-over, etc at end of interval

May resume ALL activities as tolerated AFTER 6-8 months only if…

- Equivalent LE strength and thigh circumference

- Normal ROM

- No Pain

- No effusion

- Pass Sports Test

BRACE – for 1 year during sporting activity